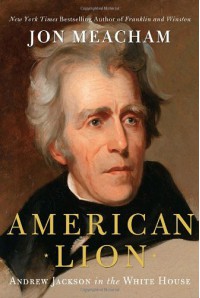

American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House

My presidential biography cycle continues with Meacham's study of Jackson's presidential years. A lot of people have been griping, particularly the first reviewer who comes up, that this book is not detailed enough and in some cases too detailed - a criticism I kind of scratch my head over upon completion. History and biography writing is a sort of art and there are several approaches: the chronologically exhaustive approach, probably most recently and popularly enshrined by Edmund Morris's three volume, three thousand page study of the life of Theodore Roosevelt and the window approach, where the author chooses prominent periods to study and analyze and of course the thematic approach. This is of the latter sort, choosing to focus not only solely on Jackson's presidential years, but mostly on the personal aspects of that time in his life, illuminated by personal correspondence. The briefest of glances at the Author's Note should make Meacham's intention readily apparent, so please, disregard the reviews of individuals who pick up books, especially academic studies, without bothering to find out the purpose of the book before devoting hours to reading its 500 pages only to be disappointed because it wasn't what they wanted.

My presidential biography cycle continues with Meacham's study of Jackson's presidential years. A lot of people have been griping, particularly the first reviewer who comes up, that this book is not detailed enough and in some cases too detailed - a criticism I kind of scratch my head over upon completion. History and biography writing is a sort of art and there are several approaches: the chronologically exhaustive approach, probably most recently and popularly enshrined by Edmund Morris's three volume, three thousand page study of the life of Theodore Roosevelt and the window approach, where the author chooses prominent periods to study and analyze and of course the thematic approach. This is of the latter sort, choosing to focus not only solely on Jackson's presidential years, but mostly on the personal aspects of that time in his life, illuminated by personal correspondence. The briefest of glances at the Author's Note should make Meacham's intention readily apparent, so please, disregard the reviews of individuals who pick up books, especially academic studies, without bothering to find out the purpose of the book before devoting hours to reading its 500 pages only to be disappointed because it wasn't what they wanted.With that out of the way, Meacham's scholarship is as impeccable as ever. I read his newest book first and I was impressed by the way he deftly intertwined the telling of Jefferson's life through primary documentation and balanced historical analysis that gave the narrative an immediacy and importance that most works of history lack outside of their introductions. American Lion is no exception. Meacham's intention was to paint Jackson as a more sympathetic figure by revealing his personal side through correspondence, diary entries and the remarks of Washington insiders and observers as he dealt with crises that every student of history is compelled to study in rather impersonal ways: the Nullification Crisis with South Carolina, a potential war with France and the Bank War. Surprise, surprise, through most of the aforementioned impersonal narrative, we are bequeathed with a rather impersonal and imposing Jackson: shrewd, cold and at times blood-thirsty and power hungry - all attributes that his contemporary opponents would have readily agreed with. Meacham paints an altogether different picture. The general who slaughtered British troops by the hundreds in the War of 1812 and Indians by the thousands, the man who sought to centralize more and more power under the auspices of the presidency, was a rather paternalistic figure. Meacham makes much of his orphanage during the American Revolution and his lack of children to define Jackson's character as familial and paternalistic. His family was his country, his constituents his children and Jackson was a man who took familial obligation seriously. The approach works rather nicely and the argument bears tremendous weight. Liberal use of personal communications reveal a warm-hearted Jackson who loved his family and took his obligations to the people very seriously. Most historical narratives have focused entirely on the public arena and in that realm, Jackson was not a trifling or warm figure. An edifice of granite and resolve, implacable and unyielding to his foes, he gained an imperial reputation. What was unknown for most of the time he was in office and for much of the time after, is that that Jackson was a construction, rationally and coldly crafted for political effect by a master statesman. Jackson was a passionate man, to be sure, but his wife's moderating influence upon him taught him to be careful who he revealed that side of himself to.

The book covers three main issues and diverges in narrative to prior formative history when appropriate to yield a context for important decisions and chances. Briefly those issues are: the Eaton affair, a social scandal that nearly made Jackson's first-term a stillborn experiment in the first widely popular election in the country's history, the Nullification Crisis, where Jackson's family, the Union, was threatened by the hostile threats of secessionists, and the Bank War, where Jackson cast himself as the will of the people made manifest in the war against plutocratic privilege in a life or death struggle for the survival of the republic. What was lacking to me in the otherwise gripping narrative, were a more extensive analysis of Indian removal and his thoughts on slavery - both of which are treated, and then dismissed after no more than a handful of pages. While Meacham readily recognizes Jackson's numerous and rather public faults, one can't escape the impression that, he's something of a Jackson apologist. Perhaps those issues were outside the purview of this particular study, but the choice of exclusion says as much about authorial intent as inclusion and study.

There's much here for the modern political scientist and social observer to find relevant. Jackson defined the modern presidency. He was the first to break the line of aristocratic philosopher-presidents that were also founders of the nation - the first pure politician rather than great thinker or intellectual architect to inhabit the office. A man of action, rather than erudition. He was the first people's president and perhaps first to feel the effects of debilitating social scandal within his administration that threatened to hamstring the entire operation of government. In many ways, the nation hasn't changed. One can't help reading about Jackson's troubles with the Eatons without thinking about the Petraeus "scandal." This is not a disparaging remark about all women, but 19th century washington socialites nearly destroyed the president of the US and made politics and the governance of the country monstrously difficult over the marital indiscretions of a cabinet member; things haven't really changed, except now the rumor mill includes about 300 million Americans, all of whom are plugged in as the social circles of Washington are laid bare by the modern media. The debate over chartering the national bank has some resonance with debate over regulation of Wall Street, the tax code and lobbying; how can Washington be expected to regulate what they themselves find 'beneficial' to their own personal good? And this is the first, in a seemingly unending series of presidents, to cast themselves as outsiders to the insider culture of Washington, with the view that their election represented a mandate to "clean things up" - a somewhat expected trope of our political cycle. It also helps to place the vehemence of modern partisan politics with threats of secession and the hanging of flags upside down and the threats of totalitarian communism and blah, blah, blah, in a historical context, for many of the same criticisms were leveled at Jackson and the behavior and rhetoric of his opponents no less incendiary or fatalistic than the language used today. We've always been a nation of extremes and half the country is always convinced that the election of the next president is going to lead to the death of the Union and our way of life and it never does. Unless, of course you're a racist slave owning plantation owner. In which case, yeah there was one election that ended your way of life (and good riddance).

Having just finished Morris's excellent Theodore Roosevelt biography, I can't help but make some comparisons between the two presidents, especially how bellicose and hawkish their images remain in the modern imagination. There are certainly shades of Roosevelt in Jackson's hawkishness, but without the naively strident and childlike militarism reminiscent of the germanic martial culture of the first half of the 20th century that marked Roosevelt's. (I guess the reasoning is, historically self-evident why that should be the case.) For jackson, force was a matter of seeking satisfaction, honor and protection rather than as a test of manhood in and of itself. As a political operative, the struggle was irrelevant to the result (as in the struggle with France over compensation as part of lingering treaty obligations). A man, according to Jackson didn't seek out violence, but wasn't afraid of it and certainly didn't rely on others to protect their personal safety and honor. In that regard, he is very similar to Roosevelt, but Roosevelt took things much farther and one can't escape a sense of childlike playing at soldier with delusions of grandeur on TR's part that encouraged him to seek out danger and violence for himself and for his family like he had something to prove.

American Lion is an eclectic melange of prominent issues during the Jackson administration rather than a thorough chronological treatment of his life. It adds depth to the historical narrative of his life and as such is highly valuable. Critics of Jackson's more controversial and less humane policies and lifestyle will feel disappointed by the lack of indictment, but the work should be valuable to them nonetheless in accepting the fact that Jackson's presidency was one of the most pivotal (in good, more than bad ways) in antebellum American history as well as probably moderating some of the vehemence of their views.